Did you know that even in 2025, millions of people in Pakistan and other low- and middle-income countries still lack access to something as fundamental as a basic wheelchair? It’s a sobering reality, especially when you consider that 15% of the world’s population lives with a disability—of which a staggering 80% reside in low-income countries like ours. These statistics struck me just days after the world observed NGO Day and International Wheelchair Day earlier this month, reinforcing the urgent need for better mobility solutions.

Wheelchairs are globally recognized symbols of inclusion and accessibility. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) dedicated to social upliftment, particularly in mobility support, exist in nearly every country. However, in Pakistan, the realities of wheelchair distribution expose deep flaws in how disability and mobility aid access are approached.

The Problem with Charitable Wheelchair Distribution

Rubina Shoaib, Founder of QasBa for Special Needs, highlights a major concern:

“Wheelchairs given to individuals with CP and other disabilities are often of the lowest quality possible. Instead of providing solutions or comfort, they create safety issues—especially when they are distributed without considering the individual’s abilities and posture needs.”

Rather than serving as a tool for empowerment, the growing trend of charitable wheelchair distribution often does more harm than good. Wheelchairs are increasingly being donated and distributed free of cost by NGOs as a charitable action. Wealthy individuals and families also contribute by donating wheelchairs directly to those they perceive as needy. However, many of these wheelchairs are of poor quality and primarily end up with post-stroke patients who belong to a more financially stable aging population—while those with lifelong mobility challenges, such as individuals with cerebral palsy, remain underserved.

The Harsh Reality of Donor-Driven Giving

Most NGOs distributing wheelchairs in Pakistan operate on donor funding, sometimes supplemented by government programs. While these initiatives claim to support individuals with disabilities, they often lack oversight, leading to serious ethical concerns about quality, accessibility, and actual impact. Not just wheelchair distribution, but all types of social welfare work is almost completely delegated to NGOs by governmental bodies, whether or not they are qualified or equipped to carry it out.

Many donors, including well-intentioned individuals, give wheelchairs without any due diligence. There are no medical assessments, no considerations for posture support or long-term usability, and no accountability for whether the wheelchair is truly beneficial to the recipient. This leads to unsafe, unusable, and even harmful mobility solutions.

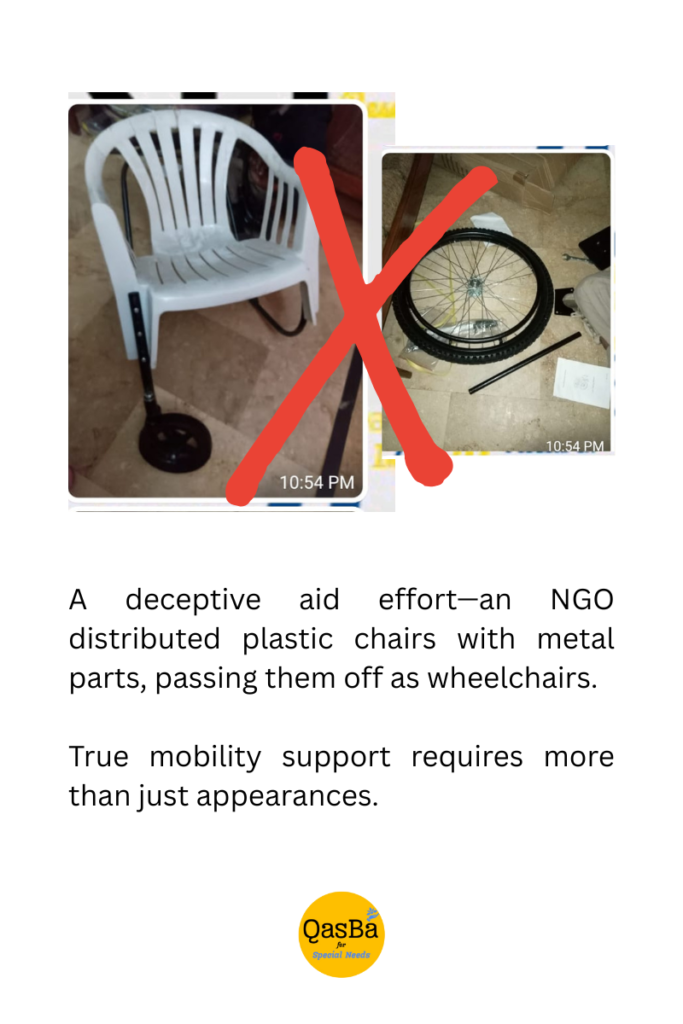

Recently, an NGO was found distributing plastic chairs with a few metal parts to be assembled as makeshift wheelchairs—an alarming example of inadequate mobility support.

Even private hospitals—including top-tier, well-funded facilities—routinely use low-quality wheelchairs. This isn’t about affordability; it’s about a systemic disregard for ethics, regulations, and responsibility. If institutions that can afford better still opt for subpar mobility aids, it raises a critical question: are we, as a society, genuinely invested in the dignity and independence of people with disabilities, or are we merely engaging in performative charity?

A recent survey by QasBa for Special Needs highlights another alarming trend: nearly all social welfare programs—whether run by the government or private NGOs—are designed with donors in mind. Their campaigns focus on attracting funding rather than serving those in need. There is no structured way for a person with a disability to request a wheelchair that meets their needs. Instead, they are left dependent on handouts, forced to accept whatever is given, no matter how inadequate.

At its core, this isn’t just a problem of resources—it’s a failure of ethics, responsibility, and respect for the dignity of people with disabilities.

The Challenge of Limited Early Intervention

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a lifelong condition affecting movement, muscle tone, and posture. Mobility is one of the biggest challenges for individuals with CP, and access to appropriate support can drastically improve their quality of life. However, in Pakistan, tailored mobility aids remain largely unavailable.

Rubina Shoaib further explains:

“At QasBa, we work with individuals impacted by Cerebral Palsy across all age groups. In 90% of cases, the condition is worsened due to a lack of early intervention during childhood. Since cerebral palsy is a lifelong condition, mobility interventions are essential to improving the quality of life for those affected.

Specialized chairs are a critical need, as individuals with Cerebral Palsy often experience involuntary movements, posture issues, scoliosis, stiff joints, and clubbed feet or hands. These individuals require semi-custom, secure chairs with belts and additional supports tailored to their unique needs.”

Without early intervention, children with CP face significant difficulties in mobility, leading to a cascading effect on their independence and overall well-being as they grow older. The lack of proper seating and positioning-support further compounds these challenges.

Why Specialized Seating Matters

Unlike standard wheelchairs, seating for individuals with CP must provide postural support, stability, and comfort. Many individuals experience involuntary movements or spasticity, making conventional wheelchairs unsafe or inadequate. A properly designed chair can prevent secondary complications such as scoliosis and joint contractures, support better posture, reducing pain and discomfort. enable greater independence in daily activities and improve access to education and social engagement. Yet, due to high costs and limited awareness, many individuals in Pakistan remain deprived of these essential mobility solutions.

Bridging the Gap

Organizations like QasBa for Special Needs are advocating for better access to mobility aids, urging policymakers, donors, and the healthcare community to recognize the urgent need for semi-custom seating solutions. Increased local production, funding for specialized mobility equipment, and training for caregivers on the proper use of these aids can make a profound difference in the lives of those with CP.

If we want to move beyond performative charity and create true inclusion, we must shift our focus from simply donating wheelchairs to ensuring that every wheelchair provided is safe, appropriate, and empowering for the user.